Obscurity in South Asia

- n4w1ds

- Mar 27, 2025

- 7 min read

Sources in each map,

Figure 1:

The epic thirty-year conflict between the Rind and Lashari tribes dominated the 15th and 16th centuries in Balochistan, a terrible civil war that would fundamentally change the Baloch tribe structure. Mir Chakar Khan Rind, who rose to head the strong Rind tribe at the young age of 18 after the death of his father Mir Shahak Khan, stood at the core of this strife. Considered a folk hero and main player in Baloch history, Chakar guided his people in what turned into a defining intra-tribal struggle for political supremacy.

Though initially motivated by rivalry for rich land, political power, and tribal supremacy, Mir Chakar Rind and Mir Gwaharam Khan Lashari's conflict started apparently over a horse-riding competition. The two tribes fought 25 separate battles between 1490 and 1518; the Rinds eventually won 15 and the Lasharis dominated in 10. Historical records state that the Rind tribe had about 40,000 fighting men while the Lasharis kept a force of about 45,000 warriors, so causing notable losses on both sides over the protracted conflict.

Following his ultimate triumph over the Lasharis, Mir Chakar Rind made the historic choice to flee his native Balochistan by 1518. Leading his people eastward, he established a new power base in the rich Punjab region. According to historical accounts, he first settled close to the Sanghar Desert, erecting almost 100 houses for his family members on what is now Tehsil Taunsa, District Dera Ghazi Khan under the name "Sowkar" (or Sokar). Later receiving a jagir (land grant) from Emperor Humayun following the fall of Sher Shah Suri's dynasty in 1556, Mir Chakar ruled this territory until his death in 1565. Eventually he became rather influential in the area.

Figure 2.

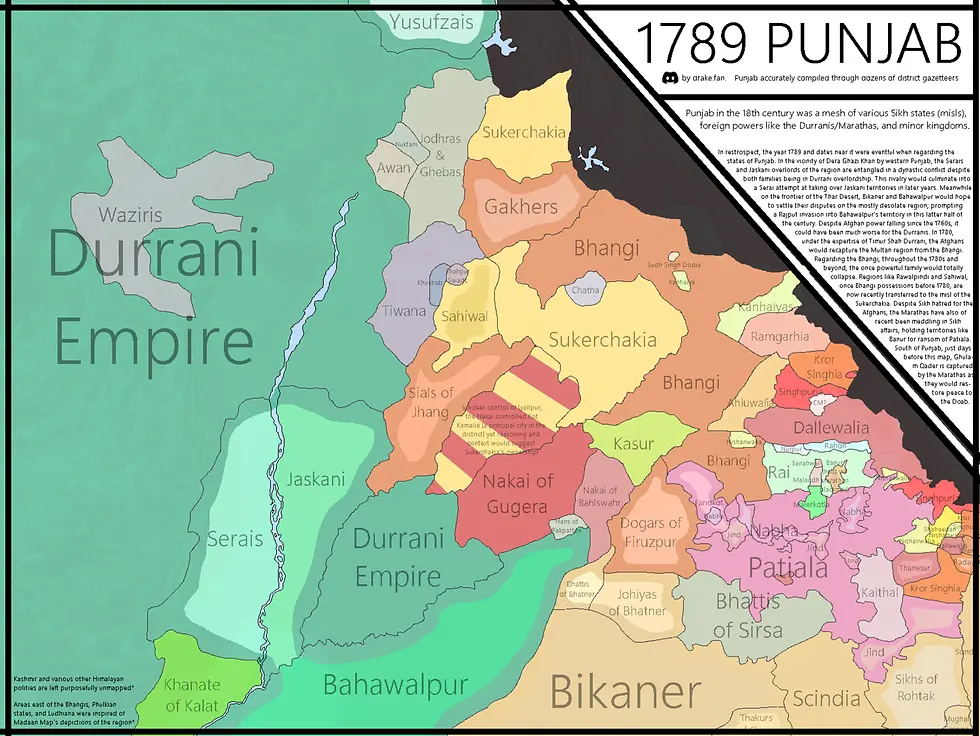

Twelve sovereign Sikh states known as Misls made up the strong alliance that dominated the Punjab region by 1789. Emerging after Mughal power fell, this unusual political system served as what Swiss adventurer Antoine Polier called a natural "aristocratic republic." Under the direction of a sardar—a misldar—each Misl was a part of a commonwealth that kept internal autonomy while presenting a united front against outside dangers. Sarbat Khalsa, the Misls' biannual legislative meetings held in Amritsar, saw group decisions about security, development, and relations with other powers made.

In 1789 Punjab, the political scene was a complex mosaic of Misl territory with different sizes, strengths, and organizational systems. As the fourth image, "1789 PUNJAB," shows, the area was "a mesh of various Sikh states (misls), foreign powers like the Durranis/Marathas, and minor kingdoms." Rising as the most potent Misl in the Majha area, the Bhangis dominated most of western Punjab between Multan and the Hill States, including major cities like Lahore and Amritsar. Among other important Misls were the Ahluwalia Misl, the Kanhaiya Misl, the Ramgarhia Misl, and the Sukerchakias—ancestors of Maharaja Ranjit Singh. By now the Misls had successfully resisted several invasions from Afghanistan, most famously driving Ahmad Shah Durrani's son Timur Shah to flee Amritsar in 1779.

By 1789, internal rivalries and territorial disputes were clearly visible even with their combined might against outside foes. As one modern source observed, "after 1767 the threat of Abdali vanished...Thus, political aspirations also woke up and selfish reasons surfaced. All misls thus began to enlarge their area of influence. Struggles between Sikh Sardars and Misls themselves rather than between Sikhs and Muslim authorities or foreign invaders marked the last quarter of the eighteenth century. These inner strife would finally prepare the ground for the ascent of Ranjit Singh of the Sukerchakia Misl, who would start consolidating authority in the 1790s and subsequently annexe most of the Misl territory, so founding the Sikh Empire in 1799 by conquering Lahore. But the Phulkian Misls south of the Sutlej would avoid this fate and finally grow princely states allied with the British.

Figure 3.

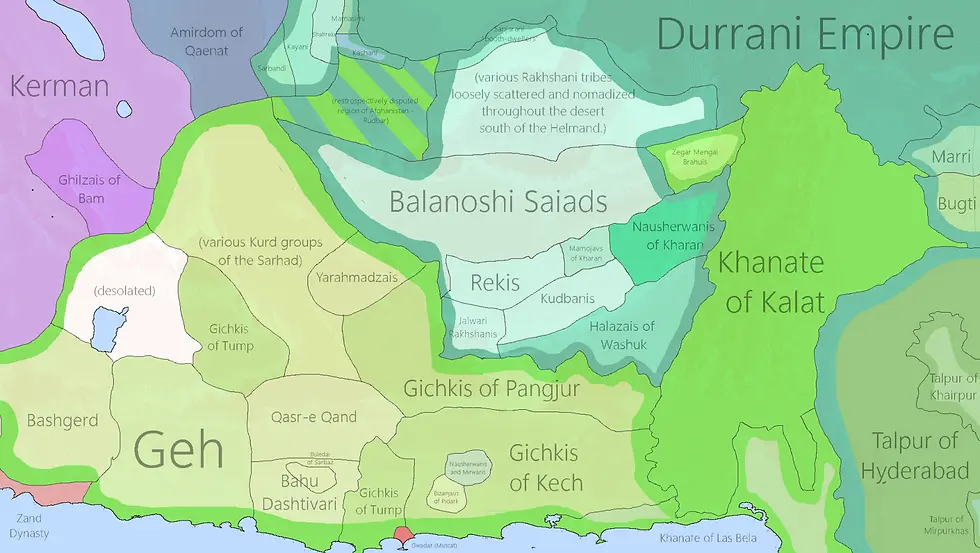

Under Mir Nasir Khan I (r. 1749-1794), Balochs knew as "The Great," the Khanate of Kalat had peaked by 1789. From its founding in 1666, this Brahui Khanate had developed into a major regional power ruling vast swaths of modern-day Balochistan across what is now Pakistan, Iran, and Afghanistan. In Iranian Balochistan, Mir Nasir Khan had united the varied Kalat region and expanded his conquests to include cities including Khash, Bampur, Qasr-e Qand, and Zahedan, so producing the most extensive and potent Khanate.

Kalat's political scene in 1789 reflected a sophisticated state structure developed by Mir Nasir Khan, who had instituted a regular standing army and built the first centralized bureaucracy in the area. Establishing the Grand Vizier to oversee state affairs, he started printing Khanate money. Most importantly, Nasir Khan had effectively given Kalat de facto freedom from the Durrani Empire. Kalat stopped paying tribute to the Durranis and kept its autonomous status, sending military contingents to the Durranis only in return for money, even if nominally acknowledging Durrani suzerainty following a 1758 treaty with Ahmad Shah Durrani.

Through diplomatic ties to the Ottoman Empire, Iran, Afghanistan, and the Sultanate of Oman, Mir Nasir Khan positioned Kalat as a regional power. He welcomed Sultan bin Ahmad, the future Sultan of Oman, and gave him the port of Gwadar (which Oman would keep until bought by Pakistan in 1958). By means of 25 military expeditions during his rule, Nasir Khan compelled the Talpur dynasty of Sindh to pay tribute, so strengthening Kalat's regional influence. In both Brahui and Baloch historical consciousness, his accomplishments in state-building, military might, and diplomatic acumen made him a central heroic figure.

Figure 4.

Established by Ahmad Shah Durrani in 1747, the once-powerful Durrani Empire had been severely disorganized by 1801 when Mahmud Shah Durrani took over from his brother Zaman Shah. Mahmud Shah marched on Kabul, then had his brother imprisoned in the Bala Hissar's top palace after defeating him. Far from bringing the broken empire together, Mahmud Shah's elevation only highlighted its scattered state, with the kingdom now split into a multitude of semi-independent chiefdoms each fighting for territory control and power.

As Zaman Shah escaped his captivity and teamed with another brother, Shuja, to oppose Mahmud's rule, the internal political climate quickly sank. Mahmud defeated this coalition, but his power was still hotly disputed from several angles. Al-Rahim, a claimed descendent of Mirwais Hotak, declared open revolt inside Afghanistan itself, effectively occupying Kandahar and besieged Ghazni while a second army marched toward Kabul. The Khan of Bukhara tried to invade Balkh. Religious tensions added to Mahmud Shah's precarious situation; news of Persian advances into Mashhad in 1803 set off reaction among Sunni religious leaders in Kabul, who encouraged attacks against the Qizilbash and Shia populations.

The instability peaked by July 1803 when Mahmud Shah's brother Shah Shujah Durrani entered Bala Hissar and released Zaman Shah from captivity. Mahmud Shah's first rule (1801–1803) thus came to an end in failure; the empire kept fragmenting. The first map's portrayal of "A Nation Divided," showing the Durrani Empire split between Mahmud Shah's occupation in the west and Zaman Shah's territories in the east, was amply demonstrated by the changing alliances and ongoing wars of this period. Mahmud Shah later returned to power between 1809 and 1818, then governed as emir of Herat until 1829. This split would still plague the area.

Figure 5.

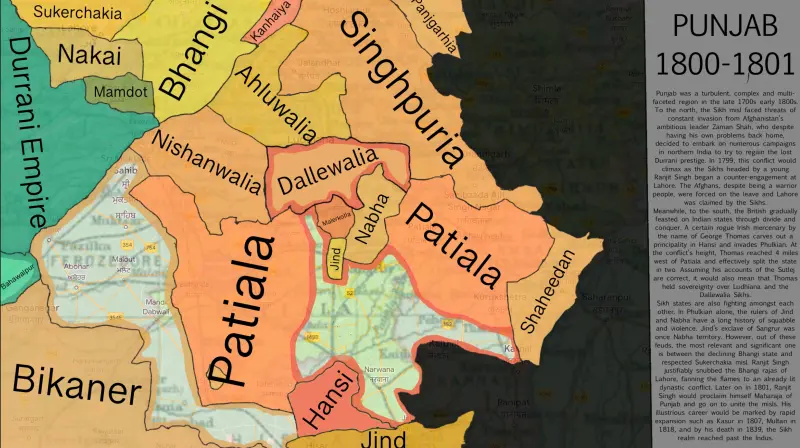

As the British East India Company grew its influence northward, the Cis-Sutlej states of Punjab—a collection of mostly Sikh principalities sandwiched between the Sutlej River to the north and the Yamuna River to the south—found themselves in a precarious political position by 1801. Emerging during the "time of troubles" following the fall of Mughal authority and the withdrawal of Ahmad Shah Durrani's Afghan army in 1761, these states—Patiala, Nabha, Jind, Kaithal, Malerkotla, Ludhiana, Kapurthala, and Faridkot—had evolved. They had been under Marathas' influence before British arrival; after a Maratha-Sikh treaty on May 10, 1785, they had become protectorate over several small Punjabi kingdoms.

As the Second Anglo-Maratha War (1803–1805) progressed and the Marathas lost these territories to the British, the political scene of the area was being fundamentally changed. Faced with the twin threat of British expansion from the south and absorption into Maharaja Ranjit Singh's expanding Sikh kingdom from the north, the Cis-Sutlej states had to make deliberate political decisions. Many of these principalities appealed to the British for protection against Ranjit Singh's ambitions for expansion, which resulted in the British gaining control over them by means of the Treaty of Amritsar in 1809, so essentially limiting Ranjit Singh's expansion south of the Sutlej River.

Internal strife among the Cis-Sutlej governments themselves, who were often involved in localized conflicts despite their ostensibly united status, further convoluted the regional order. Strategically acting as arbiters in these conflicts, the British progressively expanded their influence while preserving these states as buffer areas against other powers. Though some would survive as semi-autonomous principalities until the independence of India in 1947, following which they were arranged into the Patiala and East Punjab States Union (PEPSU), this period marked the beginning of what would become a pattern of the British using the "doctrine of lapse" to annex several of these states.

Figure 6.

For "The Great Game," the strategic conflict between the British and Russian Empires for dominance in Central Asia, the Panjdeh Incident of March 30, 1885, marked a crucial flashpoint. This crisis started when a sizable Russian army under General Komaroff completely defeated Afghan troops stationed at Penjdeh, despite their valiant resistance. With almost 1,000 men lost, the Afghan losses were notable; Russian losses stayed low. Russian troops seized the town following the triumph, leading to an international diplomatic crisis that might turn into full-scale war between Britain and Russia.

The argument focused on disputed territory including the province of Badghis and the strategic locations of Zulfikar, Ak-Robat, and Penjdeh. Prominent experts including Vambery, Rawlinson, and Malleson claim that these regions had historically been Afghan territory, having been either dependent on or subject to Herat for hundreds of years. These areas clearly had strategic value; they included rich land, close proximity to Herat and India, and the salt lakes of Er-Oilan upon which nearby populations depended. Especially, these areas had been marked on Russian staff maps inside Afghan borders until 1882, implying a conscious redining of maps to support territorial expansion.

Though both London and St. Petersburg had strong militaristic feeling after the incident, war was finally prevented by diplomatic channels. Approaching the end of his second premiership, British Prime Minister William Gladstone opposed demands for military action. The episode exposed Afghanistan's strategic weaknesses as a buffer state between growing empires and showed how local border disputes might rapidly turn into possible world crises. With consequences that would define the borders and political orientations of the area for decades to come, the Panjdeh Incident thus marks a pivotal point in the geopolitical maneuvering that defined foreign interventions in Afghanistan during the late 19th century.

In summary

From the 16th through the 19th centuries, the turbulent history of South and Central Asia exposes a constantly changing terrain of power where tribal conflicts, imperial ambitions, and newly formed nation-states woven a complex tapestry of political and military developments. From Mir Chakar Rind's tribal conflicts to the Great Game tensions of the Panjdeh Incident, these regional histories show the ongoing interaction between local power systems and more general geopolitical forces that still shape the area now.